This recycled story is from November 2019, and will hopefully entertain you with a brief smile until a new posting next week. Please enjoy.

My school grades one through eight were spent in a parochial institution of learning for wise guys. Sure there were girls that attended classes with us, but they, too, were equally guilty of driving the teaching nuns crazy.

Back then we didn’t learn about having abortions or protesting civil matters or demanding action for climate change. Rather, we studied such inane things as geography, history, arithmetic, foreign languages, art, and English.

We were expected to excel at all of these disciplines with the addition of homework that needed to be addressed at home, hence the name. The main reason for this was to see how much our parents knew, and whether or not they would help us with these extracurricular assignments.

Two different times required me asking my parents for help; one was for my Polish class, the other was for my arithmetic class.

Since both my parents and grandparents spoke fluent Polish, their help was certainly instrumental in getting a good grade in that class.

It was during my arithmetic class, however, that nerves and familial ties were threatened.

My Dad was a machinist, by trade, who used fractions every day, all day. My Mom was a housewife who excelled at taking care of the family, but didn’t need to know much about math except for making change and during cooking.

One day, I remember coming home from school with what I, in the third grade remember like I remember the thorough disciplinary beatings I received from my Dad.

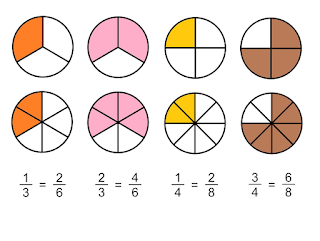

We were trying to get though something called “fractions.”

It seems as though fractions are a way to test the cohesiveness of families, and secretly conduct a comprehensive analysis of the intelligence of a student’s immediate relatives.

After nearly sixty-years, I still recall that day just as if it was hours old. Sister Agnes began drawing a circle on the blackboard. As an aside, a blackboard was what us old relics wrote on before whiteboards were invented.

Sister Agnes made that circle nearly perfect before drawing a line straight down the middle; the class carefully duplicated her every move.

She turned toward the class and told us that each side was one-half. She then turned away to secretly take a sip from what appeared to be a silver hip flask similar to that of my Grandpapa.

More lines were drawn and more sips were taken. And with each line, the class became more baffled, to the point where we all needed a sip from that flask.

My crude circle with lines made its way home with me. When my Dad finished his dinner, he asked how school was, and then asked the question for which he was sorry the rest of his life.

“Do you have any homework?”

After a few tears of failure streamed from my eyes, I produced the papers upon which the infamous circles and lines were scribbled. “Fractions,” I whispered.

My Dad didn’t have much in the way of patience, so I knew this was going to be tough.

He produced fresh paper and a pencil and began with the circles again. Again. And again.

He kept drawing circles and lines. And each circle got larger, as if it would be easier for me to comprehend it if they were more visible.

It didn’t take long before he ran out of both paper and patience.

My tears reappeared and my Dad became more contemplative.

After a break, he returned with scissors and more paper and a magic marker. The paper became a pie. He snipped long the thick, black lines, and eventually we had ourselves a two-dimensional pie with numerous slices.

As he reassembled the paper pie, the varying slices made more sense as ¼, ½, ¾, and one whole pie.

He even taught me how turn ¼ into 0.25 – fractions into decimals. After all, that was his job as a machinist.

Success, at last! But then I was diappointed because my Dad

didn’t let me have a sip from his silver hip flask.